‘Sometimes you just have to make a judgement call’: Stu Kilduff on 52 years keeping the lights on

When Stu Kilduff started work in February 1974, Christchurch’s electricity network was still a council operation, faults were logged on paper, and ABBA was on the cusp of winning the Eurovision Song Contest with Waterloo.

Nearly 52 years later, as Stu has stepped away from Orion, the company that grew out of the old Municipal Electricity Department (MED). Across five decades – multiple CEOs and restructures – and two major earthquakes, one thing has stayed constant: the quiet responsibility of keeping our community warm, safe, and connected.

“I always liked the work,” he says simply. “It gave you a sense of how important power was to people,” he adds, especially late at night, especially for the elderly.

Stu didn’t arrive via a grand career plan. He left school early, by his own admission “a bit of a ratbag,” and it was his father who pushed him toward an apprenticeship. Two job ads were cut from the newspaper: one at the MED, another with what was then NZED. He chose the MED for its variety. “House wiring, industrial, commercial, network stuff - it taught you everything.”

In the early years, that meant going into people’s homes. If a fault was traced past the network and into the house, Stu and his colleagues from the wiring department would be called. Over time, he moved from Electrician to Testing Technician, through to a stint at Connetics and back again, eventually returning to Orion in 2004 as Operations Manager. It wasn’t a role he initially wanted. His predecessor had suffered a heart attack, consumed by the pressure of trying to control everything himself.

“I’m not that sort of person,” Stu says. “Let people do their jobs.”

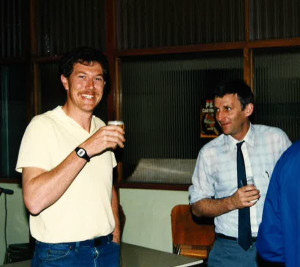

Stu Kilduff left and John O'Donnell

What changed his mind was the leadership above him. John O’Donnell, a former boss, gave him space to learn, expected high standards, and modelled calm authority. Other mentors shaped him too, particularly Colin Wright, former Control Centre Manager whose defining trait was composure.

“In my head, big disasters meant panic. Colin was the opposite. The world could be falling down, and he’d just work through it, methodically. No rushing, no yelling. Just priorities.”

That approach would be tested in September 2010, when the first Canterbury earthquake struck. Stu was woken in the early hours, pushed out of bed by the shaking. From the hills, he could see the city lights were out. He knew he’d be off to work shortly.

He arrived with a splitting headache – a night on the tiles after an All Blacks game can do that – and found himself with senior leaders looking to him for direction. Computers were barely usable, contingency plans inaccessible, but the team responded instinctively. “They just got into gear. When you get people doing what they know best, it puts them in a safe place and they perform better.”

The February 2011 earthquake caught him in Wellington, attending an emergency management meeting congratulating agencies on their response to the first quake. Phones started ringing during lunch. Christchurch had been hit again, but harder.

Getting home was chaotic. Flights grounded. The airport closed. A missed opportunity to fly on a DC-3. But eventually, Stu boarded an air ambulance and arrived back that night. By then, Orion’s control room had narrowly escaped catastrophe. The building had collapsed against the old Armagh building, preventing it from crushing the control centre entirely. Staff checked on their families first, then returned to work. The priority was safety: making sure nothing live was lying exposed, stabilising what could be stabilised.

“Electricity isn’t just lights,” Stu says. “It’s water, wastewater, communications. When you lose those, you realise electricity is an essential service.”

Some of the team couldn’t come in - their homes were destroyed, their families in need. Others stepped up without hesitation. Experienced controllers proved invaluable. Help arrived from other regions, but not everyone could cope with the relentless aftershocks.

“Within a week, some of them had to leave,” he says. “They just couldn’t handle the shaking.”

The Orion offices on Armagh Street are demolished as Stu (right) and colleagues look on

What stood out most to Stu was discipline. Despite exhaustion, trauma and pressure, the organisation recorded zero serious health and safety incidents during the response and recovery.

“That only happens if you follow the proven procedures,” he says. “Especially when things are hard.”

Those procedures, he notes, exist because people were once injured, or worse. Early in his career, safety gear was minimal. Shorts, dust coats, and hope featured heavily. He remembers near-misses that today would trigger investigations, reports and safety changes.

“We were lucky,” he says. “You wouldn’t get away with that now, and that’s a good thing.”

Over time, Stu became as known for systematic thinking during crisis response. One of his proudest achievements was leading the shift from paper-based operations to a digital network management system, not by changing how people worked, but by translating the existing operating model into an electronic environment.

“Same rules. Same process. Just in a box instead of on paper.”

The timing proved critical. When the earthquakes hit, the control room could issue hundreds of operating orders, get permits out, and deploy crews efficiently under pressure.

“Backstops matter,” Stu says. “If someone makes a mistake, the next system catches it.”

It’s also how he views technology more broadly. Automation, drones, AI – all useful tools, but never replacements for experience and judgement.

“Make the technology work for you,” he says. “Don’t work for it.”

Over his career, Stu has led teams through storms, snow, high winds, floods, earthquakes and fires. Each event, he says, is a lesson in human capability: how fatigue accumulates, when to call for help, and the value of mutual aid.

He’s had eight leadership roles over 52 years, often learning by example. Good leaders, he says, earn respect rather than demand it. Lead by example, know your team, understand the network, and stay calm.

Asked about legacy, Stu shrugs.

“Everyone gets replaced,” he says. “People move on.”

What he hopes endures is something quieter: teams empowered to make decisions, backed when they act in good faith, systems that improve performance, and a culture that treats mistakes as learning, rather than failure.

“Respect doesn’t come with position,” he says. “You earn it by how you treat people.”

As for retirement, he’s finishing work on a modest camper van, “not like one of those oversized models you see around”, he notes. The plan is to stop in places he’s driven past for decades without ever pausing.

“There’s a lot of New Zealand I’ve never actually stopped and looked at,” he says.

He’ll miss the control room. The hum of the network. The anticipation of the next big event.

“There’s still one I’ve never been part of,” he adds, half-smiling. “A black start.”

He pauses.

“I'll be p***ed off if it happens on Monday”.